The latest OECD Employment Outlook report delivers a stark verdict: advanced economies are no longer facing a shortage of jobs, but rather a shortage of workers — a direct consequence of demographic aging and declining fertility rates.

- Demographic aging is reducing the working population and threatening global growth: GDP per capita could fall by 40% by 2060.

- The dependency ratio for those over 65 rose from 19% in 1980 to 31% in 2023, and could reach 52% by 2060.

- The OECD recommends mobilizing young people, women, migrants, and seniors to compensate for the labor shortage.

- Seniors remain a key resource but face stereotypes, lack of training, and limited access to opportunities.

- AI can help, but only a comprehensive and equitable strategy can maintain prosperity and social cohesion.

A resilient but fragile labor market

In 2025, the OECD labor market remains robust. The unemployment rate stood at 4.9% in May 2025, a historically low level, while the employment rate reached 72.1% and the labor force participation rate climbed to 76.6% in the first quarter.

Yet behind these strong figures, the first signs of strain are emerging: job growth is slowing, wages are struggling to return to their pre-2021 levels, and geopolitical tensions could further undermine this fragile momentum.

Demographic aging: A historic turning point

The year 2025 marks a demographic shift. For the first time, the working-age population (20–64 years old) is beginning to decline in most OECD countries, a trend expected to continue through 2060.

At the same time, the old-age dependency ratio (the ratio of those aged 65 and over to the working-age population) had already reached 31% in 2023 and could soar to 52% by 2060, compared with just 19% in 1980. In some countries, this ratio will even exceed 70%, intensifying economic and social pressures.

Demographic aging: Economic growth at risk

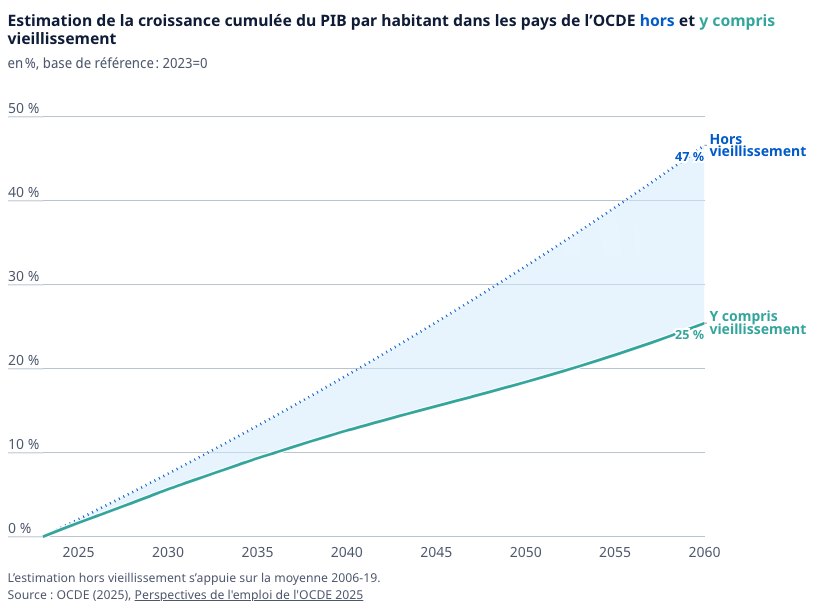

Demographic aging could significantly slow global growth. According to the OECD, annual per capita GDP growth is projected to decline from an average of 1% (2006–2019) to just 0.6% (2024–2060), a 40% drop. All OECD countries would be affected, except for Ireland and the United States.

Levers to counter the crisis

In response, the OECD calls for the urgent mobilization of untapped labor resources:

- Young people (15–29 years old): In some countries, more than 15% are neither employed nor in education or training, particularly in Spain, Italy, Greece, and Turkey.

- Migrants: Increasing migration flows to levels seen in the most open countries could boost growth by 0.08 percentage points (pp).

- Women: Narrowing the gender employment gap could add 0.2 pp to annual per capita GDP growth — and up to double that if working hours were equalized.

- Older workers: Encouraging healthy older workers to extend their careers could raise growth by 0.2 to 0.3 pp per year in many countries.

Older workers at the heart of the demographic response

Older workers are a vital resource in mitigating the effects of an aging workforce. The report emphasizes that extending their participation in the labor market would not only support growth but also help preserve valuable expertise.

However, older workers face several barriers:

- Lower participation in training programs (only one-third of those aged 60–65 in 2023, compared with more than half of those aged 25–44).

- More limited literacy and problem-solving skills.

- Persistent age-related stereotypes.

To reverse this trend, the OECD stresses the need to invest in lifelong learning, implement inclusive hiring policies, and fight against ageism, which too often hampers career progression.

AI: A tool, but not a silver bullet

Artificial intelligence could help ease workloads, extend working lives, and enhance productivity. But, the OECD warns, AI alone will not be enough to offset the structural decline in the human workforce. Without a comprehensive strategy, the slowdown in growth could threaten social cohesion and the economic sustainability of social systems.

Demographic aging: A political as well as societal challenge

Beyond the numbers, demographic aging raises a critical issue of intergenerational equity. As wealth and income increasingly concentrate among older generations, younger people are facing heightened insecurity, with more limited access to housing and stable employment.

The OECD highlights that without fair policies, the gap between generations could widen, undermining social cohesion. Reforms must therefore balance economic efficiency with fairness, ensuring that adaptation to the demographic shock benefits all age groups.

An urgent call to action

The message is clear: demographics demand a strategic shift for OECD countries. Sustaining prosperity and social cohesion will depend on the ability to extend careers, integrate more seniors, women, and migrants into the labor market, and invest in skills to keep pace with technological transformations.

The demographic crisis is not inevitable. But without swift and decisive action, it could permanently slow growth and deepen social divides across advanced economies.

Published by the Editorial Staff on